Intensity of exposure to infected meat helps determine acute disease severity, roughly categorized as light (1-10 larvae ingested), moderate (50-500 larvae ingested), and severe (>1000 larvae ingested). Patients with light infection are usually asymptomatic. Those with mild symptoms generally improve in 2-3 weeks. Patients with heavy infections may be symptomatic for 2-3 months. In rare cases of heavy infections, central nervous system (CNS) or cardio-pulmonary involvement may occur, occasionally leading to death within 4-8 weeks of infection or sooner. Patients can die from dehydration, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, encephalitis, cardiac failure, or arrhythmia.

During outbreaks, up to 20% of patients may develop severe disease, but most recover. Long-term sequelae are typically rare. If CNS is involved, sequelae may include decreased cognitive ability, numbness of hands and feet, decreased stress tolerance, loss of initiative, and depression. Otherwise may include weakness, myalgias, adrenal insufficiency, and thromboembolic disease.

There are 7 species of Trichinella pathogenic for humans; 3 important ones are Trichinella spiralis (cosmopolitan), Trichinella nativa (Arctic, sub-Arctic), and Trichinella britovi (Eurasia, Africa), all encapsulated. Trichinella spiralis is the most important; it has worldwide distribution and is often found in domestic pigs. The pig-human epidemiological pattern, which involves complex transmission routes, has diminished as the practice of feeding pigs garbage containing Trichinella-infested meat scraps has decreased.

Outbreaks tend to predominantly affect 18- to 44-year-old men, likely reflecting a higher frequency of ingesting infected meat, especially wild game. Children appear to be more resistant to infection than adults, but typical symptoms may be more intense. Children usually have fewer complications and recover rapidly. Pregnancy is associated with relatively milder symptoms, although stillbirths have been reported. Immunocompromised patients, such as kidney transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy, are at increased risk for severe infections, even with low-level ingestion of Trichinella.

The worldwide incidence of trichinellosis has declined dramatically in the past 2-3 decades because of improved inspection and management practices. Yet outbreaks still occur, most frequently in developing countries. Trichinella infection is more common in poorer regions, often where meat fed to pigs is raw or undercooked. In North America and Western Europe, the relatively small number of cases diagnosed each year (fewer than 50) typically result from eating undercooked game or bear meat, or pork from home-reared pigs.

Phases

Trichinellosis typically progresses through 3 phases, and important clinical features of acute disease, if they develop, include an enteral (intestinal) phase with diarrhea for 1-2 weeks, followed by a parenteral (invasive) phase consisting of malaise, fever, progressive (often marked) eosinophilia, and widespread myalgias for up to 8 weeks. In the parenteral phase, Trichinella larvae enter striated muscle cells, encyst (most species), and remain viable for 1 year to several years, often depending on the species.

Enteral phase:

The incubation period can last 2-50 days but typically ranges from 2-7 days. A shorter duration generally correlates with greater disease severity due to a larger larval ingestion.

Within 36 hours the larvae are freed in the stomach and go on to penetrate the small bowel wall, where they molt and become adult worms and mate. Within 1-4 weeks, the females release newborn larvae. At this stage the host immune response may be triggered and clear the infection. If this occurs, it is manifested by a non-bloody diarrhea.

Relatively small ingestions of worms generally do not cause any problems or, at most, only mild symptoms. If a sufficiently large burden of adult worms was ingested, typical features include:

- Symptoms lasting up to 7 days but possibly persisting for weeks.

- Non-bloody diarrhea – most common symptom (16%).

- Nausea (15%), vomiting (3%), constipation, anorexia, abdominal discomfort, and diffuse weakness.

- Occasionally severe enteritis from large ingestion of Trichinella, sometimes causing death from dehydration.

- Dyspnea on exertion.

- Eosinophilia

Parenteral phase:

Typically occurs from week 1-8 of infection. Involves migration of newborn larvae from the intestine to the circulatory and lymphatic systems, then to striated skeletal muscles. Associated with more symptoms. Preferred muscle groups include the tongue, diaphragm, masseter, intercostal, laryngeal, extraocular, nuchal, pectoral, deltoid, gluteus, biceps, and gastrocnemius muscles. In the myocardium and brain the parasites may disintegrate, causing intense, clinically significant inflammation, and then are reabsorbed.

Typical symptoms and signs may include:

- Fever, up to 41°C (105.8°F) in severe cases, usually beginning 2 weeks after infection and peaking at 4 weeks, with subsequent resolution. Patients with fever may appear well.

- Headache (up to 52%) worsened by head movement.

- Severe widespread myalgia (up to 89%), especially when breathing, chewing, or using large muscles, coupled with muscle weakness.

- Ocular signs – peri-orbital edema, subconjunctival hemorrhage, conjunctivitis, chemosis, disturbed vision, restricted ocular movements (paresis) with ocular pain and diplopia. Retinitis is rare. (Note: periorbital edema, somewhat peculiar to trichinellosis, may be due to an allergic-like reaction.)

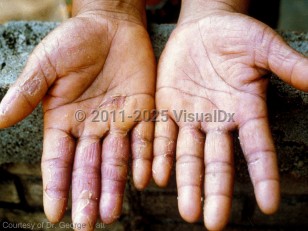

- Cutaneous signs – facial edema (may render the patient unrecognizable), hand swelling with palmar (volar) surface erythema and focal desquamation, and subungual "splinter" hemorrhages resembling bacterial endocarditis.

- Urticarial and morbilliform (measles-like) rashes are uncommon.

- Eosinophilia increases greatly during the parenteral phase.

- CNS involvement, which occurs in 10%-24% of these cases, often with meningoencephalitic signs and with a mortality rate of 50%. Deafness and monoparesis are rare.

- Cardiac involvement occurs in the third week of infection, with a mortality rate of 0.1%. Death often occurs during weeks 4-8 of infection, resulting from myocarditis, congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, or a combination thereof.

- Pulmonary involvement (33%), especially of the diaphragm, complicated by pneumonitis or bronchopneumonia may present as dyspnea, cough, or hoarseness.

- Death, although uncommon, typically occurs in the fourth to eighth week of infection, sooner if due to arrhythmias. Deaths are more common among older adults.

Involves larvae encystment and muscle repair, and may continue for months to years after infection. Encystment can lead to cachexia, edema, and extreme dehydration. Symptoms usually decrease around the second month for T spiralis.