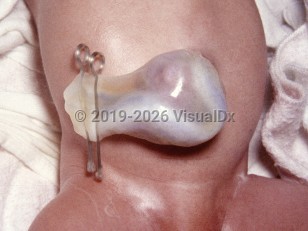

Normal embryonic herniation into the umbilical cord occurs around 6-10 weeks of development, after which the intestines return to the abdominal cavity. An omphalocele occurs when the intestines do not return into the abdomen. The condition is typically sporadic with rare familial cases. Etiology is unknown, although it has been associated with increasing maternal age.

Omphaloceles are seen on ultrasonography at 14-18 weeks in about 1 in 1100 pregnancies. The incidence in live births, however, is about 1 in 4000 due to both spontaneous and medical pregnancy terminations.

In more than half of omphaloceles, other structural malformations are present, including cardiac and gastrointestinal tract anomalies and pulmonary hypoplasia. Any associated malformations are the primary determinants of patient outcome.

Syndromes associated with omphaloceles include:

- Beckwith-Wiedemann – omphalocele, macroglossia, gigantism, pancreatic islet cell hyperplasia, and predisposition to tumor development

- Pentalogy of Cantrell – omphalocele, Morgagni diaphragmatic hernia, sternal defect, pericardial defect, and congenital heart abnormalities

- Omphalocele-exstrophy-imperforate anus-spinal (OEIS) complex – omphalocele, exstrophy of the cloaca or bladder, imperforate anus, and spinal defects

When the omphalocele is small, and there are no associated physiological or chromosomal abnormalities, prognosis is good. Most infants recover with no long-term consequences. One concern may be the cosmetic appearance, due to lack of umbilicus and scar.

Infants with larger omphaloceles may have gastroesophageal reflux, feeding disorders leading to failure to thrive, and adhesive bowel obstruction. Most improve with time, or can be treated.

The overall recurrence risk of omphalocele in subsequent pregnancies is less than 1%.